Ebola crisis

On January 22nd, 2022, a lorry from Mauritius carrying 100 Cynomolgus monkeys (AKA crab-eating macaque or long-tailed macaque), on their way to a CDC quarantine facility, crashed on a highway in Pennsylvania, US. At the time, a woman stopped to help and was hissed at by one of the monkeys. It was later reported that she got sick; developing a cough and pink eye. She was given four rabies jabs and anti-viral drugs. As several monkeys had escaped, local residents were warned not to approach or attempt to come into contact with the monkeys and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), police and firfighters searched for the monkeys using thermal imaging technology.

The accident reminded me of an incident that occurred way back in October 1989 in Reston, near Washington, DC, US. Like the incident in Pennsylvania, the danger appeared in the form of 100 monkeys that were delivered to the Reston Primate Quarantine Unit - a facility demolished in 1995. It was a one-storey building owned by Hazleton Research Products, which specialized in importing animals for medical research.

The monkeys came from the tropical rainforests of the Philippines where they were crated, flown to Amsterdam, then flown to New York's JFK Airport, and driven in the back of a truck to Reston, 255 miles away.

DYING MONKEYS

By the time the monkeys arrived at Reston, two of them were dead. Animals often died from the stress of travel so this was not unusual. However, by November 1st, another 27 had bled to death.

Reston's director, Dan Dalgard, thought it could be simian haemorrhagic fever (SHF), which can decimate monkey colonies, although cannot be caught by humans. On November 2nd, another shipment of monkeys arrived from the Philippines. Dalgard housed the consignment several rooms away from the infected monkeys, which were now dying 1-2 per day.

On November 13th, Dalgard carried out an autopsy on one of the monkeys and sent a spleen sample to the CDC in Atlanta. Four days later, Dalgard had all of the first group of monkeys put down. But, on November 25th, the new shipment started to die and two of the caretakers reported sick with flu-like symptoms.

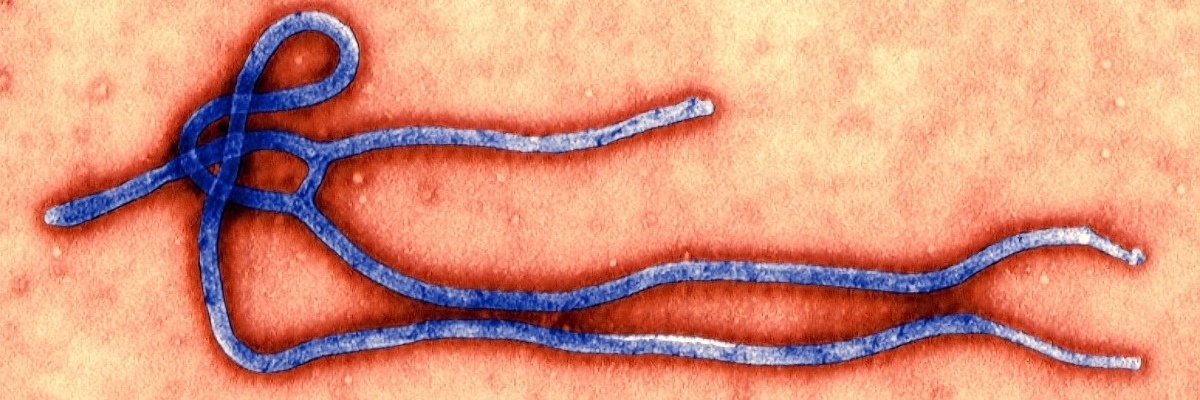

On November 27th, the CDC found the monkeys were infected with Ebola (filovirus)(EBOV). This deadly disease had so far been restricted to Africa. The Reston monkeys came from the Philippines. Moreover, it was thought that the 'filovirus' was transmitted by blood-to-blood contact only.

AIRBORNE DISASTER

This new strain of Ebola strain was airborne and could spread just like a common cold. The CDC formed a biohazard team with the Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. The caretakers were isolated in hospital and monkeys were sealed off. The biohazard team killed, performed autopsy's and incinerated every monkey in the building and they found Ebola in every specimen. They also sealed every possible opening to the outside world. They scoured the walls, floors and ceilings with bleach, then fumigated the entire building with disinfectant gas.

NON-FATAL

It was thought that Reston was now safe. However, on January 12th, 1990, more Philippine monkeys came down with Ebola. This time they closed the building and let the virus do its work. All the monkeys died and the building was pronounced safe again. Meanwhile, the caretakers made a complete recovery. Their immune systems successfully fought the Reston strain of the disease. As the virus had mutated and become airborne, it had also become non-fatal to humans.

As the Reston incident proved 30 years ago and the pandemic from 2020, our ability to deal with such killer viruses is frighteningly inadequate. Although we talk hopefully about treatments for the Human Immuno-deficiency Virus (HIV) - at Biosafety Level 2/3 on the virus danger scale - like the recent CROI 2022 dual stem cell transplantation successes carried out by The International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trial Network (IMPAACT) P1107, scientists acknowledge the impossibility of finding a cure for the Level 1 common cold. So what can be done to combat Level 4 viruses?

SEARCH FOR A CURE

Although there is no cure for Ebola, tests have been developed for the early detection of viral ribo-nucleic acid (RNA) via real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) during acute infection. However, the earliest window for viral RNA detection in blood samples is 48–72 hours after the onset of symptoms. It is vital the disease can be diagnosed in its early stages, when symptoms may seem no worse than a bout of flu, it will at least be possible to quickly isolate sufferers.

To be successful, a parasite must not kill its host. This is a lesson that Ebola has yet to learn. The sheer speed at which they kill means that outbreaks tend to burn out before developing into epidemics. This is why HIV has spread to all parts of the world - it takes a long time to die from it, giving the virus more time to move on.

Another point in our favour is that scientists have successfully overcome one Level 4 virus. Variola, the smallpox virus which killed millions before it was defeated by the development of a vaccine from cowpox. Scientists hope they will eventually find similar vaccines for Ebola and its relatives.

A MAN-MADE PROBLEM

Ironically, modern medicine and technology may be responsible for inadvertently spreading these diseases. Regarding the Covid-19 pandemic, The World Health Organisation (WHO) said, "The first cases of 2019-nCoV confirmed in Europe were not unexpected, and they remind us that the global nature of travels exempts no country from infectious disease spread." As global demand for medical research increases, more monkeys are being transported across the world bringing previously unknown diseases out of their habitat. In seeking cures for old diseases, we may well be exposing ourselves to new ones.

Until the monkeys, which died at Reston, were diagnosed with Ebola, nobody thought the virus was present in South East Asia and scientists are still guessing how the disease got there from Africa.

IMPENDING DISASTER

The most frightening aspect of these killer viruses, however, is their ability to mutate. The Reston incident demonstrated graphically to scientists that if a Level 4 virus becomes airborne, it is almost impossible to control, as did Covid-19.

Fortunately, the Reston strain of Ebola mutated in such a way as to be harmless to humans. But what if Ebola Zaire, which kills nine out of ten infected people, evolved into an airborne strain? To put that into perspective, Covid-19 kills around one in 80 infected people world-wide.

In 1990, Dr Hiroshi Nakajima, Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO) said, "We stand on the brink of a global crisis in infectious diseases... no country can any longer afford to ignore their threat". This statement is eerily similar to what those in Governments around the world have been saying during the Covid-19 pandemic.

LEARNING FROM HISTORY

But what if terrorists were to get hold of these diseases? The AUM Shinrikyu cult, which unleashed nerve gas on the Tokyo subway system in March 1995, was also developing biological weapons. That same month, Larry Harris, a microbiologist and member of Aryan Nations, a white supremacists' group, was arrested in the US for illegally procuring freeze-dried bacteria that cause bubonic plague.

The 'what if' scenarios are as varied as they are terrifying, but we are still more likely to die from almost anything other than a Level 4 virus. Malaria, measles, meningitis, cancer - which may also be caused by viruses are far more probable killers.

In a speech in November 1994, Nobel Prize winner Joshua Lederberg warned of the increasing threat from microscopic predators. "We're not alone at the top of the food chain," Lederberg says. "We have been neglectful of the microbes, and that is a recurrent theme that is coming back to haunt us."

The WHO made a statement in 2009 warning of a novel influenza A virus H1N1 strain. They said, "The world is now at the start of the 2009 influenza pandemic." Although this strain killed a small number of people.

EBOLA CURE IN 1995?

In the May 1995, during the Ebola outbreak in Kikwit, Zaire, Nicole, a nurse in the local hospital, came down with the virus. The Nigerian doctors gave her a blood transfusion from one of the few patients who had recovered from the disease. The CDC doctors thought the health risk involved in the transfusion would almost certainly kill her. But Nicole survived, as did seven out of the eight other patients who received transfusions. Still, the CDC experts are reluctant to pronounce this a cure since the transfused blood had not been screened for other diseases and the transfusions were not conducted under laboratory conditions.

It appears that scientists have been racing against time for over 30 years to find cures for these new killers, as more 'old' diseases, such as tuberculosis and malaria, are proving resistant to antibiotics. But there is always hope.